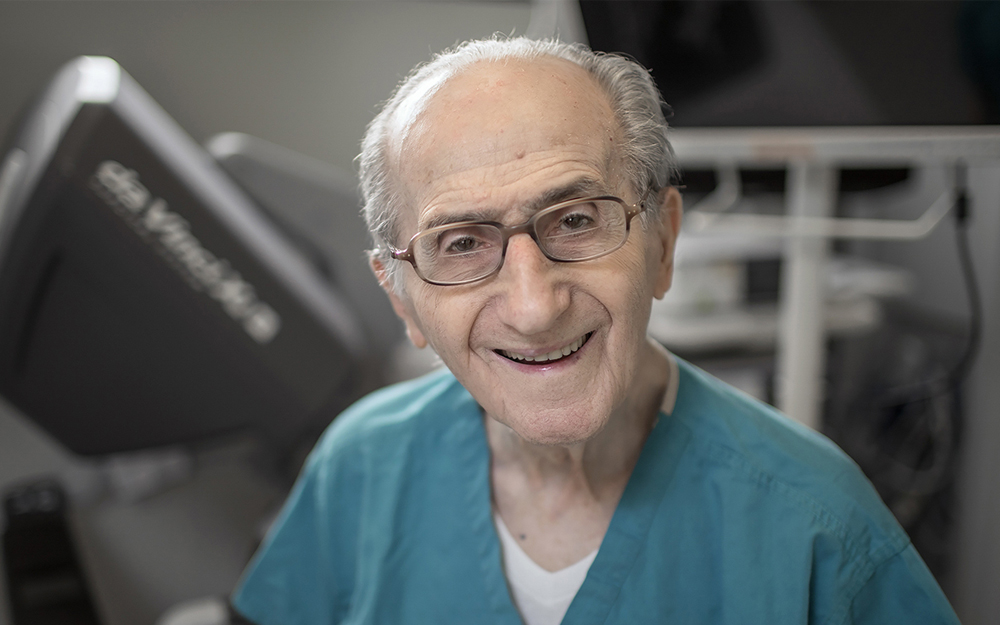

The Incredible Life of Dr. George Berci

Few people can boast a more accomplished life than Dr. George Berci. Perhaps best known for his groundbreaking work in the field of endoscopic surgery, Dr. Berci is so much more—an accomplished violinist, Holocaust survivor, medical pioneer, and worldly scholar to name just a few. We had the immense honor of speaking to the 99-year-old surgeon and current staff member of Cedars Sinai, Los Angeles for a conversation about his extraordinary life.

You once mentioned that you played violin for Bronislaw Huberman. What was that like?

I don’t remember all the details, because this was when I was about 15 years old. At the moment I am 99 years old.

I grew up in a family of musicians—when I was just 3 years old my family told me I had to pick up an instrument. My grandfather was a French hornist and my father was a symphony timpanist. When I was 10 or 11 I started performing violin concertos, and by 14 or 15 I was performing professionally. This was around the time I started hearing of this man named Bronisław Huberman—he was very well known for the concerts he would play in Vienna. I ended up meeting him there at the Vienna Academy of Music, where he took me in.

The first thing we played together was the Bach Charconne. A few minutes in, he stops playing and tells me, “Well… this is no Bach!” Not long after that, I became the concertmaster of the high school in Vienna.

Do you have a favorite composer?

I love the music of Bach. I’m especially in awe of the violin concertos—I can still whistle them you know! A few others are Mendelssohn, Tchaikovsky… my greatest memories in life are of music.

What is a musical memory that is particularly meaningful to you?

I have great memories of Yehudi Menuhum, Jascha Haifetz, and of course, Bronisław Huberman.

Is there a connection between medicine and music?

I remember the story of a famous plastic surgeon named Theodor Billroth who was a close friend of Brahms. He was a very important member of the music community of Vienna and studied music through his relationship with the great composer. There has not been many papers or studies that I know of that focus on how music and medicine are intertwined, but I think it is a very worthwhile topic to study. I’m just finishing a book—which I found 40 years ago—written by a surgeon who came from a musical background like myself. I found this very interesting because, nowadays, doctors rarely come from a place of musicality.

What is your Musical story?

Ages ago, when I immigrated to Australia from Hungary in 1956, I started to play in the chamber orchestra there. I took on a fellowship there that helped pave the way to my playing here in America.

For as long as I have lived here, I have been very involved in endoscopic surgery, which is a type of method that allows you to put a telescoping camera into hard-to-reach areas (the body has many of them). So I took my violin with me, and decided to use this technology to look deep inside the instrument. I did this also with cellos, violas, and other instruments because I had never looked inside before. It was amazing—I was out of this world with excitement.

I intended to publish a paper about this subject—and not even as a joke! It was to my disappointment to soon find that someone else had published a paper about the same exact thing. Now I sit here today with that same violin on my desk.

What advice do you have for young people in this difficult time?

Well, nobody really knows what is going on. The first thing is to survive, because we don’t know what will happen. After that, we need to teach music to our young people. That is very important—music can illuminate lives in ways very few things can.

Read more about our incredible community!

COEXISTENCE THROUGH MUSIC

Each year, the KeyNote program reaches more than 22,500 children in Israel.

Read More